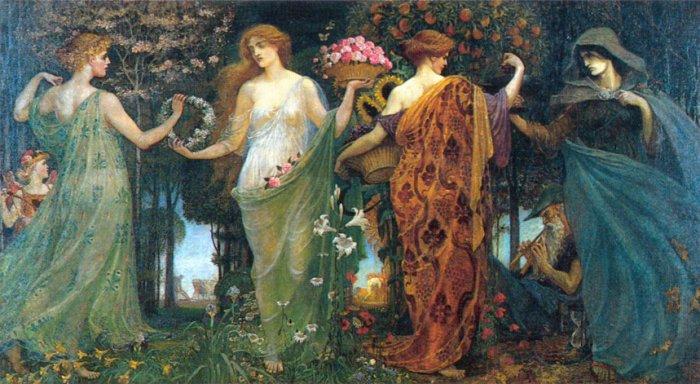

The forests of the fairy tale, and these are the fairy tales we get from the Germanic tradition, the Brothers Grimm, were collected at a time when the folk and oral traditions were dying out. The brothers, like many intellectuals of the day, were inspired to collect the tales which they regarded as a ‘pure’ form of culture; in this they were not unlike Wordsworth and Coleridge, who wrote the Lyrical Ballards which were a reaction against the highly-stylised poetry of Pope, Spencer, etc.

These young writers and academics were sickened by the corruption of the elite and yearned for a time when people could return to a ‘simpler life’. Nothing ever changes right? So they thought that they would go around to record the stories of the ‘folk’ – hence the name, folktales.

This was not just an act of nostalgia, but revolution. The Romantics – think Beethoven, Wagner, Verdi – were now experiencing the fervour of rebellion against their aristocratic overlords, and these stories were meant to show that these simple tales were just as relevant as the ‘high culture’ which were enjoyed by the upper classes and capture that deep indigenous knowledge.

Yeats and other Irish artists did the same thing and for the same reason – which is just as well, as many of the Irish myths and legends were recorded by them before they disappeared for good.

The fairy tales the brothers collected had been knocking about for centuries and it has now been verified that they are one of our oldest myths and stories. They are in fact so old that the characters in them are NOT real people but archetypes. An archetype is a symbol of a quality which lies inside all of us. So the dragon, king, queen, princess, etc they all operate on a symbolic level and they all live within.

Children, of course, understand this. Children do not take these stories literally and it is the job of adults not to take them literally. They know that the thrill and the delight, but also the safety, of the encounters with the Big Bad Wolf. The Big Bad Wolf is not out there, it is inside each of us, as Angela Carter’s wonderful interpretation of the ‘Red Riding Hood’ story shows – being ‘hairy on the inside’.

The wicked stepmother is not a real person, but an expression of antipathy – the antipathy we need to go out into the world, sometimes forced out – to learn something. To struggle. We then make our way back home, to the Father, the home – reunited, but changed. And where is the Mother? Like the Earth, the Mother is the element which invisibly journeys with us, that holds us.

But because they are also archetypes, all of these are found inside each and every one of us.

Thus, when we tell stories to children, especially fairy tales, we are introducing them to an age old form of the narrative. One where there is peril and danger, the breaking of bonds, casting out into the wilderness, battle and struggle, fortitude and courage, overcoming and finally evolution and change.

That is the power of the story.

So fairy tales do many complex things in a very efficient amount of time. This is why they work so beautifully. They are like pebbles, well worn by time into beautiful pieces of art. Of course we don’t do something as silly as tell children why we tell them this or over explain anything. There is no need to.

Children simply receive the story as it is in order to interpret it for their own age. And you can be sure that it isn’t the age which you or I were born in. They figure out the meaning for themselves. They have to. Just as the children in the fairy tales battle their way out of the murk.

That is the beauty of the fairy tale.

/coniferous-56a0a0843df78cafdaa36833.jpg)

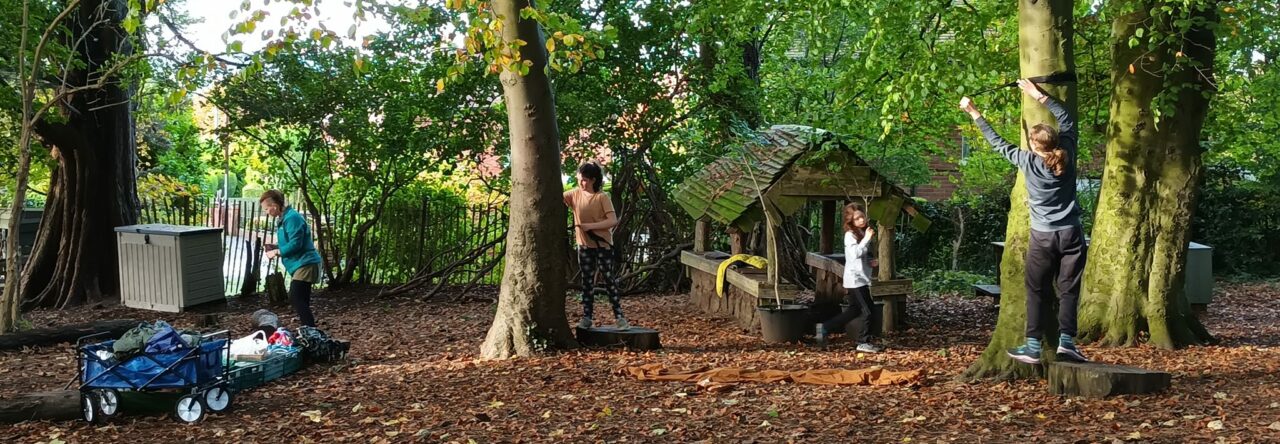

What inspired this post? Well, today we were scouting Hillsbrough Forest and because it used to be a commercial forest, there were deciduous as well as coniferous trees. (Oddly there weren’t very many native woodland trees, but no matter.) The contrast between the two types of forests is always startling.

The light and life in a deciduous forest which loses its leaves annually is in sharp contrast to the dark tall coniferous trees which keep theirs. The straight, narrow fast-growing trees which make them so commercially attractive crowd together to shut out the light and it is in THESE forests – think of the Black Forests 0f Germany – which these stories take place.

The trees all look alike, their uniformity is unending and if you do not know your way around, you could, like babes in the woods, get lost. In many ways, that is a metaphor for life.

During many Forest School sessions, I have sat in both kinds of forests and told stories, and always those stories mean a little more than they would in the comfort and safety of being tucked up nicely in bed. Forest School brings the immediacy of the habitat, the unhemlich nature of the place, where the whispering wind through the leaves, the rustlings and sussurations, murmurings and stirrings, lend themselves to the telling of the tale.

We tell stories in Elements because stories are what give our lives meaning. They inspire us, keep as as warm as campfire glows, lend us courage when we need it most. These are the thoughts behind the stories we tell. I thought it would be nice to capture them on a page.

Stephanie Sim